"Buck the System!" Leastwise I think that's what they said.

Part 1: A rare historical event. The elements of change. Globalizers Assemble. More sensible souls push back. And an imagined conversation about it all.

We - you, me, everyone - are right in the middle of a rare historical event. After all, it’s not every generation that gets to experience an inflection point. A true inflection point, that is. It doesn’t happen very often. Just once every few hundred years.

We tend to think of changes in our world as having to do with factors that are external to ourselves - changes in our environment, maybe, but not in us ourselves. It’s the new technology. It’s the new government. It’s the new whatever … but we humans are still the same, aren’t we? Well, are we?

Now, I’m going to try to make some behavioral linkages across very long periods of time, hundreds of years, which you might think strange … mad, even … in a world that often seems to believe that anything that happened up until yesterday must be irrelevant today. Well, so be it. Maybe I am bonkers.

The point is, we are now all accustomed to the fact that technologically-led change happens on a more or less continuous basis. But I think it fair to say that we do not pause to ponder whether or not the internal human operating system undergoes any fundamental changes.

The question is: are you and I running the same brain-ware as humans did five hundred, a thousand, two thousand years ago? And, if not, what changes might have taken place?

It was the English historian Frances Yates (1899-1981) who, when writing about changes at the time of the Renaissance, identified what she called …

… inner deep-seated changes in the psyche during the early seventeenth century.1

Subsequently, American literary critic Lionel Trilling (1905-1975) agreed that …

… something like a mutation in human nature took place.2

‘A mutation in human nature’, huh?

Is this what happens at these particular inflection points? Well, maybe. In fact, we might label these particular periods of time ‘spasms’ because they are not necessarily comfortable!

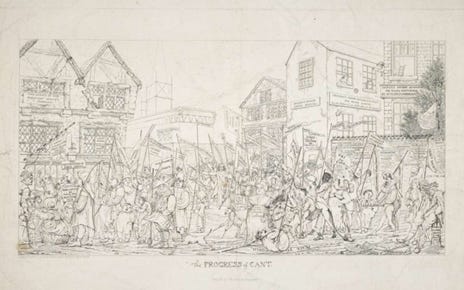

The last occasion before the current spasm happened around two centuries ago. Lord Byron was furious about it and labelled it “The Age of Cant”. The Age of Hypocrisy, that is. Thomas Hood even produced a satirical etching titled “The Progress of Cant” (1825) that’s now in the V&A in London.

This supports a key point about these mega-change spasms: they are not only about new technology. Sure, new tech is always a key factor but there’s always more to it than that. In fact, I’ve come to the conclusion that there seem always to be three factors:

A significant new technology

A socio-moral eruption or moral spasm

Censorship

The three factors are always present when a mega-change happens, and each happens via an introductory ‘transformation window’ of typically 50 to 75 years.

The key point, in my opinion, is that there is a danger that we fixate on the technological advances without taking proper account of the socio-moral changes.

What follows is a thumbnail of the most recent three ‘spasms’ (that of the present day and the previous two) to explore something of the complexity.

Printing with movable type & the power of the individual 1450-1520

First, let’s go back to when printing was invented, with an introductory transformation window dating around 1450 to 1520 in Europe. The transformation was initiated by Gutenberg’s invention of printing with movable type (1455 in the Rhineland city of Mainz) and Luther’s Protestant Reformation (1517).

Printing caused huge consternation among the elites. In Europe, the ruling Roman Catholic authorities were terrified that the broad availability of a mass communication system capable of producing texts in different languages might rob them of the power that, up until that time, had safeguarded their possession of arcane knowledge.

A key indicator of fact that this was ‘a proper spasm’ is that it led, in 1486, to the setting-up of Europe’s first ever censorship office, operated jointly by the electorate of Mainz and the city of Frankfurt. Censorship is a feature of all major transitional spasms. If a transformation is under way, some form of censorship will be in evidence!

Mind you, it wasn’t just Christendom that was affected: the Islamic authorities went further, putting in place a ban on printing that remained all the way through to the nineteenth century.

The censorship, however, did not stop the utterly convinced and abrasive Martin Luther (1483-1546) from promoting his view that salvation was not necessarily dependent upon the Roman Catholic Church:

For the pope is not above but under the word of God.3

The moral panic at the heart of this European transformation related to the shift from belief in the absolute power of the medieval Christian Church, to the revolutionary concept that, using God-given ingenuity, humans could master the world in which we live. It was not a rejection of religious belief, but a repositioning of it.

The Protestant assertion of faith as a personal and private matter was on the march. Printing was on the march, too. In short order, presses arrived in Basle (1466), Rome (1467), Paris (1470), Cracow (1474), London (1476) ... and on and on.

Thus was the world turned upside-down, in this instance flipping the power dynamic from top-down to bottom-up.

It was the result of a combination of a revolutionary technological development, a counter-view to a dominant philosophy that had, so to speak, passed its use-by date, and a liberal helping of illiberal censorship! Ring any bells?

The Boulton & Watt steam engine & the Age of Cant 1775 – 1825

Then it happened again with the arrival of the mechanical-industrial age. This convulsed the Europe (including, for example, the French Revolution – 1789) and America (the American Revolutionary War – 1775-1783) and was powered by a plethora of thinkers including Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), David Hume (1711-1776), Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), Thomas Paine (1737-1809), Adam Smith (1723-1790), Voltaire (1694-1778) and more.

Arguably, the specific tech advance that triggered this transformation was Boulton & Watt’s perfected steam engine (1775) accompanied by a moral panic to reform the …

manners and morals amid the Sodom and Gomorrah of ... Britain.4

This all happened, of course, contemporaneously with the publishing of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations and a multitude of contributions from the philosophers and politicians listed above.

It was another door-opening to a new world but, at the outset, the general discourse was NOT all about the advances in technology. Rather, it was about social behaviour and morality – especially the issue of ‘cant’ (OED: affected or insincere phraseology; esp. language implying piety which does not exist; hypocrisy). Think the vile Uriah Heep in Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield (1849-50).

We can learn a lot from the reactions of one notable commentator who lived exclusively within this transformation window period: George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (1788-1824). During his short life, Lord Byron achieved fame for his poetic genius (although in 1822 The Examiner declared “No work of modern days has been so cried out against as immoral and indecent as Don Juan” and Lady Liddell told her daughter, “Don’t look at him. He is dangerous to look at”), notoriety for his sexual adventures (Lady Caroline Lamb famously asserted that Byron was “mad, bad and dangerous to know”), and a legacy of bravery (his death came about through injury and sepsis when engaged in helping the Greeks fight back against the colonizing Sunni Islam state, the Ottoman Empire).

At this time, the liberality or grossness, depending on which way you view it, of the Georgian period was being supplanted by the more prudish and not infrequently hypocritical attitudes that came to personify the Victorians.

The more puritanical folks did perhaps have a point because some of the ‘liberal’ behavior appears definitely to have been excessive. For example, the greatly lauded English Shakespearean actor, Edmund Kean …

In the interval of a play, and sometimes between scenes, he would have sex with a prostitute, sometimes two or three.5

The change of moral mood caused him to be vilified in a campaign by The Times of London. Byron’s behaviour also came in for criticism, which is when he hit back with his “age of cant” riposte. Twitter/X-style comments, it seems, are not as new a thing as one might imagine.

This was the genesis of what was to become the morally rigid but commercially productive Victorian period, infused with the Protestant work ethic. In 1838, the year of Queen Victoria’s coronation, a historian of rural customs wrote …

We are become a sober people. England is no longer Merry England, but busy England; England full of wealth and poverty – extravagance and care.6

It was the start of the modern era, including the nation states and social mores and business formats that grew to dominate the 20th century. And it moved the power dynamic needle further towards the bottom-up end of the scale.

Digitalization, now with added AI and quantum computing & critical theory 1970 – 2030 (?)

We than arrive at the present day. The technology this time holds out the promise of an utterly transformed, digitalized future supercharged by AI and quant computing.

Digital tech was around before the 1970s, but the event that seems to mark the transition from digital infancy to an independently developing digital world happened in November 1971 with the launch of Intel’s 4-bit 0.1MHz 4004 microprocessor, a ‘micro-programmable computer on a chip’, the enabler of microcomputers. At the time, the vast majority of people were unaware of its existence, let alone its importance.

And the moral panic? A hugely complicated one this time because the tech and the politics of post-Second World War Europe with, subsequently, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990/91, combined to directly enable and promote what for some is the dream and for others the nightmare of globalization.

It all led to a preemptive top-down global push by numerous ‘elites’ - a selective one-way push into the West, the West having been viewed as somehow having benefited unfairly from the advances of the previous spasms. Which, I guess, is why no-one thus far has suggested that globalization might also involve people from the West moving to wherever else in the world they might choose. Syria or North Korea, anyone?

However, the global project could really only work if it was agreed to by everyone, everywhere. And it wasn’t and isn’t. So, a counter-push was surely inevitable. Which is why this spasm has attempted to push the power dynamic needle back towards the top-down end of the scale.

As you may already have gathered from the foregoing, the moral component of these spasms always to come down to some expression of a contest between bottom-up and top-down governance. Let’s look a little more closely at that element …

SPASM THE FIRST: PRINTING & INDIVIDUALISM

As indicated earlier, the first of the spasms that I’ve outlined was accompanied by a bottom-up political push for individual power as represented by the successful Protestant onslaught against the Roman Catholic church of that time. And perhaps because England had, from the 12th and 13th centuries, pioneered individualism it seems to have found particular acceptance there: freedom of the individual … the right to own property … increasing liberty and prosperity.

SPASM THE SECOND, STEAM POWER & YET MORE INDIVIDUALISM

In the West, the second spasm further entrenched the individualism and, thereby, the dominance of bottom-up governance. This was the age of the Protestant work ethic and an increased laissez-faire approach. Which is to say, a push yet further in the direction of bottom-up governance.

By its very nature this inevitably sustained inequality: the rich were free to get richer and the poor were free to get poorer. This led, perhaps inevitably, to development and promotion of Socialist counter systems, most notably, the top-down collectivist system of Communism as devised by Karl Marx.

SPASM THE THIRD, DIGITALIZATION & A TOP-DOWN COUNTERBLAST

In the aftermath of the Second World War, an increased sense of the horror and futility of warfare led to the founding of the United Nations and what would become the European Union.

Then, in 1989, with the collapse of the Soviet Union in sight, the West was able to claim victory in the Cold War. Western liberal democracy appeared to have seen off all comers and Francis Fukuyama could announce “the end of history” concept:

What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of postwar history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.7

A tad premature, don’t you think!

My own take on this is that two different and largely opposing strands of thought and activity came into play, and ended up making a kind of common cause - a version of the ‘my enemy’s enemy is my friend’ principle in order to change the power dynamic back towards a top-down directed governance.

Here’s how it might have happened …

When Western victory in the Cold War was declared, the two strands were:

The jubilant Western Liberal Democracy fans (WLD), particularly Big Business: “Let the goldrush commence!”

The seething Global Virtuous Socialism fans (GVS): “You think we’re beaten? Think again!”

The WLD

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s the Western Liberal Democracy fans, confident in their victory, set about outsourcing manufacturing and other activities around the world, deindustrializing vast areas of the West in the process. After China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, it became a major beneficiary of this activity.

The transition was aided and abetted by management consultancies. Seeing the opportunities before them, they enthusiastically got involved: to the extent, for example, that they even devised new methodologies. For example, Rajat Gupta and Anil Kumar at McKinsey & Company actually ‘invented’ Knowledge Process Outsourcing (KPO) and Business Process Outsourcing (BPO).

For many Western businesses, “globalization” post-1990 was, I believe, a euphemism for Western expansion. And it happened very fast. For example, the grand opening of McDonald’s first outlet in Russia, in Moscow’s Pushkin Square, happened as early as 31 January 1990. In the following decade, U.S. retailer Best Buy made a big move into China … but the attempt foundered. (I’ll write more about this separately.)

Outsourcing meant that the West lost many millions of jobs and large areas remain hollowed out.

The GVS

Meanwhile, many of the convinced promoters of socialism and communism were seething with discontent. But they’d seen the writing on the wall some years since and had been quietly preparing their fight-back since the 1960s.

Many of these Global Virtuous Socialism fans were bright bunnies tucked away in the cloisters of academe. To many of them, it was obvious that, regardless of the way that things had turned out, their socialist concepts were more equitable and kinder than the arbitrary cut-and-thrust of free markets.

And although they of course would not talk about it because it was simply a side effect, the top-down nature of their preferred solution meant that they stood to gain more because their longed-for ‘equitable paradise’ would require an expert-class of elites to ensure its smooth operation. They certainly didn’t want any latter-day kulaks screwing up the fairness and equity of it all!

All they needed was a mantra and an argument.

The mantra was the easy bit. If their opponents pointed out that twentieth century socialist/communist experiments in Russia, China and elsewhere hadn’t worked out too well, they chanted, “It hasn’t been done properly yet.”

The argument, beyond that bald claim, was rather more tricky. So, to start, they dropped the notion, used by Marx and others, that it was all about the economy, and switched their attention to broader societal issues.

To support this, they needed a means to counter the prevailing views of where the West was headed, to counter the views that had delivered the successes of the Enlightenment, to counter the Western Liberal Democracy fans.

That meant demolishing the idea that bottom-up individualism and freedom was best and, even, pushing aside the moderating influence of communitarianism, which holds that individuals thrive best in communities.

What would work? The answer lay in the post-war coming-together of the world: “Well, just look at the world! It’s obvious, isn’t it? Look at the inequalities. Look at the unfairness. Look at the cruelty. But we’re all human … we’re all the same … we’re all citizens of the world.”

So, these two groups, the jubilant Western Liberal Democracy fans and the seething Global Virtuous Socialism fans, realized that they did actually share a goal - Globalization. And although some may have somehow managed to believe in both solutions, the majority differed regarding the main aims and outcome of that globalization.

Here’s how I imagine the conversation might have gone …

Western Liberal Democracy fans - WLD: Hey, we both want globalization, and that’s surely enough to get on with, isn’t it?

Global Virtuous Socialism fans - GVS: We don’t trust your motives. You just want to make a lot of money. You don’t care about the really important things like kindness and compassion.

WLD: How can you say such a thing! We’re bringing jobs and prosperity to the whole world and, to support it all, we need a really great global supply chain. So doesn’t that mean we’re bringing kindness and compassion to the global workforce? … except maybe for the working class in the West … admittedly we’ve stiffed them a bit but …

GVS: Oh, that’s okay, we don’t mind that. But around the rest of the world it’s only good if it’s done properly.

WLD: What does that mean?

GVS: Well, there are several really big issues. Sustainability … Climate … Equity …

WLD: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Okay, okay … (Pause. Thinks.) Listen, what if we mandate some of that stuff as part of general business practice?

GVS (cautiously interested): How do you mean?

WLD: Well, we want to have a flourishing global system and, to be honest, it’ll help us to have a few .. ahem … ‘levers’ to justify our necessary global control.

GVS (definitely interested): Global control, eh?

WLD: Mmm, necessary global control … to make sure it’s all running properly … purely in the public interest, of course … the greater good, and all that.

GVS: Of course. Of course. (Pause) How about we start with things like Diversity, Environmental, Equity, Governance, Inclusion, Social …

WLD: Whoa! Whoa! Too much, too much! People can’t handle it all. They like threes … three-letter initialisms, that is. Simple as A-B-C. W-T-O World Trade Organization. C-E-O Chief Executive Officer.

GVS: L-O-L … Laughing Out Loud.

WLD: Exactly.

GVS: Okay, what about Diversity … Inclusion … Equity?

WLD: Nearly, but that gives you an unfortunate acronym, doesn’t it - D-I-E.

GVS: Ooh, fair point. Let’s go D-E-I then … Diversity, Equity, Inclusion … that covers off the stuff around organizational frameworks and fairness and full participation.

WLD: Okay, except it doesn’t, really, does it?

GVS: What do you mean?

WLD: It’s just that it seems to exclude Meritocracy so that’s a restriction on full participation, isn’t it?

GVS (shrugging shoulders): It’s meritocracy that’s got us into the mess we’re in now.

WLD (puzzled): Oh, I see.

GVS: Yeah. Anyway, let’s go with DEI and, maybe, Environmental, Social & Governance - E.S.G - would that work?

WLD: Sounds fine - we can say that ESG covers off all the bit about Sustainability. Good. Do you know, I really, really like these.

GVS: Really? I must say I rather expected you to be somewhat resistant. What makes you so happy about it all?

WLD: I can answer that with just two letters … H and R.

GVS: H.R. What, the HR departments?

WLD: Yup, just think about it, we’ve had HR departments since forever - we’ve had to have them because of all the routine form-filling that’s needed, and the occasional “there, there” when, you know, somebody grazes their knee in the factory or something.

GVS: You make it sound like an old-style school matron.

WLD: Do I? Well, maybe. But this new stuff is just marvelous, particularly back here in the West because it can soak up a load of the folks who’ve been laid off since we shut everything down here. Give ‘em something to do, and give ‘em a few dollars to spend on all the stuff we ship in from everywhere else.

GVS: Well, I’m pleased you’re pleased.

WLD: Pleased? I love it.

GVS: And I like the global control aspect.

WLD: Necessary global control. Don’t forget the ‘necessary’ - keeps it all above board. D’you know, I think we’re going to get on famously, old chap.

GVS: Whoops, just a word of caution there. Don’t call me ‘chap’. You have no idea what my gender might be.

WLD: W-T-F!

More on this in Part 2 of this series.

Thanks for reading.

Frances Yates, quoted in Trilling (2)

Lionel Trilling. Sincerity and Authenticity (1971, 1972)

From The Proceedings of Friar Martin Luther, Augustinian, with the Lord Apostolic Legate at Augsburg in Luther’s Works (Minneapolis, 1957-1986). Quoted by Tom Holland in Dominion: the making of the western mind (2019)

Ben Wilson. The Making of Victorian Values: Decency and Dissent in Britain 1789-1837 (2007)

Ben Wilson. Ibid.

Ben Wilson. Ibid.

Francis Fukuyama. The End of History? (1989)

I really like part 1; a tour de force of the REAL inflexions in human history. I agree that nothing changed until the invention of "Printing with movable type & the power of the individual 1450-1520" and "The Boulton & Watt steam engine & the Age of Cant 1775 – 1825" except the invention of data movement via electricity, I think, was significant too.

I look forward to Part 2.