When Worlds Collide ... where's Flash Gordon when you need him?

The A-B-C of Civilizational Collapse #2

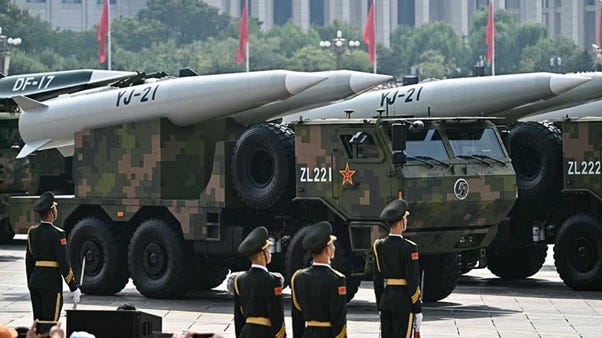

It was interesting, was it not, to see footage from the China Victory Day Parade of 03 September 2025? Officially titled the Conference to Commemorate the 80th Anniversary of the Victory of the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War (perhaps it jumps off the page rather more snappily when viewed in Chinese characters?) one surely can’t help thinking it was also a hypersonic-missile-tipped middle finger to the West: “Stick that in your Unipolar pipe and smoke it.” All fronted by Xi Jinping, President of the People’s Republic of China, flanked by Russia’s Vladimir Putin and North Korea’s Kim Jong Un. Not quite what historian Francis Fukuyama had in mind, methinks, when, in 1989, he wrote:

[T]he century that began full of self-confidence in the ultimate triumph of Western liberal democracy seems at its close to be returning full circle to where it started: not to an "end of ideology" or a convergence between capitalism and socialism, as earlier predicted, but to an unabashed victory of economic and political liberalism. (My emphasis)

Hmm, an online check tells me …

… the Chinese political system is considered authoritarian.

… the Russian system is described as an authoritarian dictatorship.

… the North Korean system is labeled a totalitarian dictatorship.

Not much “economic and political liberalism” there!

However, look on the bright side: put these players alongside the liberal democratic parts of the world, and the social-reforming progressives, and … ooh … let’s not forget the theocratic authoritarians, and the rest, and it means that there really, truly, genuinely appears to be a proper spectrum of political diversity. And diversity, as we are all frequently assured, is our strength.

So, presumably that’s good, isn’t it?

As ever, I’m trying to make some sense of what’s going on in the world, writing aloud to try to fathom what appears, prima facie at least, to be a lot of thinking and behaviour that might be accurately described as insane. I’m doing this from the perspective of eight decades spent here on planet Earth, augmented by a fairly voracious appetite for reading and learning about the broader historical context. I’m perfectly aware that this does not necessarily mean that any conclusions I reach will necessarily be ‘right’, whatever that means, but I hope they might be of some relevance, even if it’s only to point out where I’m going wrong.

I popped into the world just after the end of the Second World War and grew up in the UK at a time when the conflict’s scars were still clearly in evidence in the landscape (for example, I can confirm from first-hand experience that bomb craters make great children’s playgrounds), in the economy (Britain was beyond flat broke), and in the people (where there was ample evidence of both pride and pain).

But we’d done it! Well, I hadn’t, obviously. But my parents’ generation had. They’d ensured the continuance of democracy in the West and the freedoms that accompany it. In fact I think it fair to say that they were even more determined than before to promote those ideals. Why? Because nearly everyone, of high or low estate, rich or poor, had played their part and surely, therefore, deserved to share in the resulting opportunities?

However, somewhere along the line, it all went awry. I kind of woke up to this fact in the 1990s but wiser folk had recognized the problem much earlier. In 1969, for instance, the British art historian, Kenneth Clark (1903-1983), in a superb television series titled Civilisation commented on the fact that the Western world was losing confidence in itself:

[I]t is a lack of confidence, more than anything else, that kills a civilisation. We can destroy ourselves by cynicism and disillusion, just as effectively as by bombs.

Nonetheless, it took me until the 1990s, specifically December 1991 when the dissolution of the Soviet Union occurred, to get any real sense of the issue. By that time I was doing a lot of writing work for management consultancy Accenture and found that an ever-increasing amount of my time was devoted to writing reports and articles and management materials about Outsourcing.

From a personal point of view it served me extremely well, thank you very much, providing a remarkably reliable stream of fees across an enormous range of projects.

However, as I wrote about more and more companies relocating their manufacturing and other functions around the world, I did start to wonder about the longer-term outcomes for the millions of people who were losing their livelihoods right across the West.

But the Big Daddy of the second half of 20th century business and management analysis, Peter Drucker (1909-2005), seemed fairly sanguine about it all. In the 1990s he predicted that the Western world would thrive in the twenty-first century because of ‘knowledge work’. The implication was that the work that was being outsourced was the dirty work, the cheap stuff, the grunt work. BUT, apparently … drum roll … there would be lots of lovely, clean, high-value, high-reward, “knowledge work” for us Westerners to do:

The most valuable assets of a 20th-century company were its production equipment. The most valuable asset of a 21st-century institution, whether business or nonbusiness, will be its knowledge workers and their productivity.1

So that was alright then, wasn’t it? I mean, Drucker was usually right - a sensible, reliable, trusted voice on matters corporate.

Then, on 11th December 2001, China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO). The whole project went on steroids.

Just a few months earlier, in March 2001, William Jefferson Clinton, 42nd president of the United States, assured an audience at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland:

By joining the WTO, China is not simply agreeing to import more of our products; it is agreeing to import one of democracy’s most cherished values: economic freedom. The more China liberalizes its economy, the more fully it will liberate the potential of its people – their initiative, their imagination, their remarkable spirit of enterprise. And when individuals have the power, not just to dream but to realize their dreams, they will demand a greater say.

Dream on, baby! Subsequently, as author Stewart Paterson wrote:

If the intention of the West was to mould China in its own image, the policy has been counterproductive. By enabling a rapid rise in living standards in China without political change, trade and investment have helped validate the policies of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and legitimize the regime.2

Regardless or perhaps because of this the march of Outsourcing continued aided by ever-more astoundingly clever technology that enabled ‘distributed enterprises’ to function as or more efficiently than their formerly co-located versions … and access lower cost labour into the bargain. It all meant that, for many companies there were lightning-quick wins that delivered enhanced profits … and bigger bonuses! All of which, in turn, encouraged more and more de-industrialization and hollowing-out of the industrial areas of the West.

Here are three snapshots of the outcomes. First, a UK example where author Ben Judah refers to Harlesden, North London:

Once there were enormous industrial estates along the thundering lines into London, thumping tracks wider than the Thames. Railway cars would unload ton upon ton of Sheffield steel and Durham coal. These were the big mass jobs where, in the 1950s, the Jamaicans and the Irish became British: working on huge lines in the plants with other men who got you to go to the football or the pub. But those industrial estates have almost all shuttered. There are no more production lines in Harlesden now: Poles, Somalis, Nigerians – these men work alone, atomized as pickers, drivers, cleaners, builders.3

Second, a French perspective from 2019:

Entire areas of production in the West have still collapsed, though, especially in textiles, footwear, household appliances, chemicals, timber, plastics and rubber. Thirty years of political passivity have produced a less rosy outcome than that promised by champions of pain-free deindustrialisation. France has had a trade deficit since 2004; the surplus in services does not compensate for the deficit in manufactured goods. Factory closures have turned whole regions into jobless deserts where technical skills have been lost. Service sector salaries, which were supposed to make up for job losses in industry, are on average 20% lower than those in manufacturing.4

And, finally in this trio, a 2019 comment from the U.S.:

Dependence on imports has virtually eliminated the nation’s ability to manufacture large flat-screen displays, smartphones, many advanced materials and packaged semiconductors. The U.S. now lacks the capacity to manufacture many next-generation and emerging technologies. This is to say nothing of the human suffering and sociopolitical upheaval that have resulted from the hollowing out of entire regional economies. Once vibrant communities in the so-called Rust Belt have lost population and income as large factories and their many supporting suppliers have closed. ... In terms of long-term competitiveness, the biggest strategic consequence of this profound decline in American manufacturing might be the loss of our ability to innovate—that is, to translate inventions into production. We have lost much of our capacity to physically build what results from our world-leading investments in research and development. A study of 150 production-related hardware startups that emerged from research at MIT found that most of them scaled up production offshore to get access to production capabilities, suppliers and lead customers.5

With these snapshots in mind, think once again about the 2025 China Victory Day Parade. Does it prompt a few questions? Perhaps …

Did no-one think about the implications of mass Outsourcing for the well-being of millions of citizens in the West?

Did no-one think about the national security status of the deindustrializing countries?

Did no one think, at a point in time when the West had thrown millions of people out of work, to question whether it was a good time to start importing millions more? Might it have been better to encourage the incomers to use the opportunities made newly available by the amazing technologies to help build shiny new commercial capabilities within their own territories? After all, that’s what China and a few others did.

This seems to me to leave two further questions.

Was there some Big Agenda going on here?

And, of course, there was or is! In a word - Globalization. I’ll come onto that next, but just before I do …Doesn’t President Trump deserve some credit for acting to reverse some of the issues noted above?

In Part 1 of this ABC of Civilizational Collapse I suggested Western civilization is being subjected to a post-‘end-of-history’, three-element Demolition Process as follows:

A. The general promotion of Globalization and a “new world order” which, it seems to me, has ended up being promoted by two distinct groups - the Post-Humanists and the Islamists. These two couldn’t be more antithetical if they tried but, at this stage, they appear to find it useful to accommodate one another. Each perhaps believes it can give the old heave-ho to the other later in the game?

B. A range of destabilization activities, with two main strands. One: a decades-long academic campaign to brainwash younger generations and discombobulate older generations of Westerners by radically redefining the basic building blocks of Western society … repositioning much of Western history as evil … restating former certainties (e.g. there are two genders) as false … and positioning everything in terms of oppressed versus oppressors within a therapeutic framework. Two: the movement of people from other cultures (other worlds) into the West in large numbers as an attempted fait accompli to kick-start and lock in the destabilization and homogenization processes. Both of these strands seem to have been initiated by the Post-Humanists, with the Islamists seeing the opportunity to take advantage of the situation and probably thinking it to be divine providence?

C. Concurrent with A and B, a decades-long campaigns of undermining and bureaucratization of the democratic systems of the West to create an all-encompassing fog as a cover-up for the advancement of the entire project.

Here, in Part 2 of the series, let’s focus on the A of that A-B-C, the first and positioning stage, The Globalization Project itself.

As you may already have gathered from the odd sarcastic comment or two, or three, I am not now nor have ever been a fan of the full-fat Globalization Project. By all means be concerned about the global dimension of anything and everything, and show respect, love even, towards everyone, but do not eradicate the validity of component human populations and their specific histories and traditions in the process.

The current experiment of bringing numerous human societies into the West en masse seems likely to result in one of two outcomes, or some combination thereof: either Balkanization so that there are numerous closed, potentially ‘no-go-area’, communities, or, as the enfant terrible Renaud Camus suggests, a homogenized people-soup. Alongside the Balkanization and homogenization, I guess one group might go for a preemptive takeover of the whole bag of tricks.

Does that perhaps merit a little more explanation?

Okay, here’s my theory …

Earlier, I made the point that in the aftermath of the Second World War there was a heightened sense of a mood of peace and love: “No more conflict, thank you very much. We’ve had enough of that. Now, we want to live in harmony.”

This desire was made explicit and tangible shortly after the end of the Second World War when, in October 1945, the United Nations came into being. Its very existence implied that greater attention would be given to the welfare of all people - a fact that, in and of itself, was wholly commendable.

Meanwhile, out in the business world, IBM had delivered its first Harvard Mark 1 machine in 1944. Then, in 1948, Bell Labs announced the first transistor. Which is to say, the march of digital technology had started.

Over the next two decades things progressed but then in November 1971 a world-changing event occurred - the launch of a ‘micro-programmable computer on a chip’, Intel’s 4-bit 0.1MHz 4004 microprocessor, the enabler of microcomputers.

In January of that same year, a new business had been formed in Switzerland - The World Economic Forum.

So, at first quietly and relatively slowly, the wherewithal to do entirely new things in the business world was becoming a reality. This fact alone would raise fundamental questions about the conduct of Business.

The point was, the modern business corporation had been created as a mechanism of the nation-state, to help improve the welfare of its citizens.6 But now, all of a sudden it seemed, it was possible for a business to a) distribute more and more of its elements and functions anywhere and everywhere around the globe without loss of cohesion or efficiency and thereby b) completely transcend nation-states.

What were the implications of this for polity?

A variety of conversations arose but we humans aren’t great at forecasting the outcomes from new technological capabilities. ‘Twas ever thus. After all, it is extremely hard to predict what will be possible as a result of a technology that never previously existed. You have only to review what happened in the aftermath of the invention of the printing press. And then again when the steam engine and other means of ramping up power came along. Confusion! Disagreement! Polarization! Social disorder! Censorship! Violence!

And, of course, it’s happening all over again on this occasion. In fact, the disruption and disorientation is the biggest yet because, this time round, it damn well affects the entire world.

There are, of course, always those who take the Panglossian view that “All is for the best in the best of all possible worlds.” I do not share this idealistic view. I align more with Voltaire himself when, near the conclusion of Candide, he wrote:

One day the old woman ventured to remark: ‘I should like to know which is worse: to be raped a hundred times by pirates, and have a buttock cur off, and run the gauntlet of the Bulgars, and be flogged and hanged in an auto-da-fé, and be dissected, and have to row in a galley - in short, to undergo all the miseries we have each of us suffered - or simply to sit here and do nothing?’ - ‘That is a hard question,’ said Candide.

… Pangloss conceded that he had suffered horribly, all his life, but having once maintained that everything was going splendidly he would continue to do so, while believing nothing of the kind. 7

A key point, it seems to me, is that nothing about what is going on at the moment comes anywhere near the dream that some idealists have of cosmopolitanism.

The cosmopolitan (from the Greek for ‘citizen of the world’) ideal has a long history. In the first century BCE, Diogenes the Cynic claimed to be a citizen of the world but he lived in a barrel so why not?

Later, mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Leibniz (1646-1716) thought that the world God had created must, by definition, be “the best possible world” … which opened the way for the splendid and merciless satire that Voltaire (1694-1778) created in Candide, as per the fragment quoted above.

But that hasn’t stopped some folks, today, hankering for the dream of world-citizenship to become a reality. It’s perhaps inevitable because there are many more of us around (an eight-fold increase in the human population in the past 200 years) and our scientific and technological know-how now gives us global reach and startlingly novel functionality.

The tech is important to the proponents’ argument from both the positive and negative perspectives. Positively, it is argued, global tech and all that it enables means that everyone, everywhere should and can have the flexibility to live wherever they choose. Negatively, the technological sophistication is used by some to plant fear in people’s hearts: if we can be made to ditch all rationality and not just deal with, but worry ourselves to death about, pandemics, climate change, runaway AI developments and so on, the easier it might be to persuade us that human affairs are now only really manageable on a top-down, globally-governed basis.

At which point, let me re-state my usual qualification that, as ever, so much depends upon the choice between a top-down or a bottom-up view of the issue. The macro view, or the micro view - which is it to be? What’s needed, of course, is a combination of the two.

Anyway, back to cosmopolitanism. A leading exponent of globalized cosmopolitanism is Kwame Anthony Appiah, and very humane about it all he is, too:

… the basic idea of the metaphor of global citizenship is that we should think of one another as humans, as having the kinds of connections and responsibilities to one another that we have with our literal fellow citizens - the people who are literally citizens of our own polis, our own city, our own state. So what does that mean in practice? I think there are two strands here. One is a cosmopolitan has to think that everybody matters: you’re engaged with, you worry about, everybody on the planet. … But the second thing, and what’s distinctive about cosmopolitanism, I think, is that cosmopolitans think that you can be engaged with, care about and otherwise interact with people in positive ways without wanting them to become like you. Cosmopolitans enjoy the fact, value the fact, that human beings make different decisions about how to live and we want to live in a world with people who are not the same as ourselves. (You Tube, Library of Congress file, Jan 2025)

There is surely little to argue about with that explication? It’s really quite sane and humane. However, the general problem is that, nearly always, we humans do not behave like that. Rather, when worlds collide we want to impose one system over another, ‘our’ system over ‘their’ system. Such moves - power grabs - are always made for either material or ideological gains.

Power Grabs ‘R’ Us

Power grabs are the very stuff of human history, and they are always made for material or ideological gains … sometimes, both.

Arguably, the material option - simple, unalloyed grabs of territory, goods, money - is the least dangerous: any specific instance of it may be horrible but at least you know where you stand. But when ideology comes into play all bets are off and the potential for evil ramps up.

Take, for example, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022. From the Western perspective it appeared to be an unprovoked land grab. That’s bad enough, after all the nation-state system depends upon countries respecting one another’s territorial integrity … but it was sort of comprehensible. However, if you revisited a speech made by Vladimir Putin just six months earlier, a far more ideological justification was set out:

Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians are all descendants of Ancient Rus, which was the largest state in Europe. Slavic and other tribes across the vast territory – from Ladoga, Novgorod, and Pskov to Kiev and Chernigov – were bound together by one language (which we now refer to as Old Russian), economic ties, the rule of the princes of the Rurik dynasty, and – after the baptism of Rus – the Orthodox faith. The spiritual choice made by St. Vladimir, who was both Prince of Novgorod and Grand Prince of Kiev, still largely determines our affinity today.

The throne of Kiev held a dominant position in Ancient Rus. This had been the custom since the late 9th century. The Tale of Bygone Years captured for posterity the words of Oleg the Prophet about Kiev, “Let it be the mother of all Russian cities.”

Ideology! … therein lies the power to completely dehumanize an enemy in order to maintain a hideous level of violence and killing across a long period of time.

The same applies, of course, in the war that Israel is fighting against Hamas. It couldn’t be more ideological if it tried: after all, Hamas was actually created with the goal of wiping Israel off the map.

And, in a different ideological direction, the World Economic Forum is a strong supporter of economic globalization. But, in a 2020 book titled The Great Reset, Klaus Schwab, the founder and until recently president of WEF, wrote about the “globalization trilemma” posited by Harvard economist Dani Rodrik:

The trilemma suggests that the three notions of economic globalization, political democracy and the nation state are mutually irreconcilable, based on the logic that only two can effectively co-exist at any given time. 8

So, there you are, in their view the nation state is the one to ditch. If that is done, they believe, economic globalization can proceed, accompanied by an increasingly widespread deployment of technologies directly associated with individuals to improve health and efficiency … a.k.a. Transhumanism.

Mind you, here’s what Russian philosopher Alexander Dugin makes of that:

In the eyes of the globalists, other traditional civilisations, cultures and societies are also to be subject to dismantling, reformatting and transformation into an undifferentiated global cosmopolitan mass, and in the near future to be replaced by new - post-human - forms of life, organisms, mechanisms, or their hybrids. 9

Well, I don’t know about that but it sure makes clear that the Western ‘end of history’, victory of liberal democracy narrative ain’t the only story. Indeed, the views from around the world are so different that it seems reasonable to say that it is analogous to worlds colliding.

When Worlds Collide

Time, I think, to draw the threads to a close insofar as this post is concerned, which brings me to idea of the collision of worlds.

When the sci-fi novel When Worlds Collide was published in 1933 it really struck a chord, as is evidenced by the fact that the central theme of having an athletic hero and his mate escaping the doomed Earth to find a habitable one was taken up the very next year, 1934, by writer Alex Raymond in the comic strip Flash Gordon. Subsequently, in 1938, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster launched Superman.

I suggest that, right now, we humans find ourselves playing yet again with the idea of colliding worlds - but this time it really is true and it really is global.

The old order that evolved over the past millennium resulted in a world of nation states that aligned themselves, if Samuel Huntington had the right of it, across nine distinct ‘civilizations’ and practiced the several different political systems that I’ve alluded to throughout this post.

Today, in the aftermath of the ‘end of history’, it seems to me that the world is challenged by several new worlds that are on a direct collision course with the status quo and with one another:

The Globalists (Economic Power & Transhumanism version)

The Globalists (Cosmopolitan Dreamers version)

The Pursuers of Dar al-Islam

I’ve briefly discussed the Globalists so what about those who pursue Dar al-Islam? Here’s Wikipedia’s introduction to the topic:

In classical Islamic law,, there are two major divisions of the world which are dar al-Islam (lit. ‘territory of Islam’), denoting regions where Islamic law prevails, and dar al-harb (lit. territory of war), denoting lands which have not concluded an armistice with dar al-Islam and lands that were once a part of the dar al-Islam, but no longer are. Muslims regard Islam as a universal religion and believe it to be the rightful law for all humankind. Muslims are imposed to spread Sharia law and sovereignty through lesser jihad against dar al-harb. According to Islam, this should first be attempted peacefully through Dawah. In the case of war, Muslims are imposed to eliminate fighters until they surrender or seek peace and pay the Jizya if subdued.

So, what’s now going on? We Westerners have been making such a mess of defending our achievements that it seems quite possible to me that the more dedicated adherents of Islam are taking advantage of our cynicism and disillusion which, as Kenneth Clark said, are quite as effective as bombs.

We know that Islam is a proselytizing religion that has had its sights set on Europe for more than a thousand years. But it is not just a religion; it is also a political system and a social system. And, so far as I understand it, it is very dogmatic about all of it. So, it is very, very hard to see how that can meld with any other system.

As Afghan-American author, Tamim Ansary, writes in his superb 2009 book Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World Through Islamic Eyes:

I don’t see how a single society can be constructed in which some citizens think the whole world should be divided into a women’s realm and a men’s realm, and others think the genders should be blended into a single social realm wherein men and women walk the same streets, shop the same shops, eat at the same restaurants, sit together in the same classrooms, and do the same jobs. It can only be one or the other. It can’t be both.

So, what are we to make of all this?

Well, personally, I don’t fancy any of the three options that I listed above. The motivation behind Economic Globalism is, I sense, driven by greed. Cosmopolitan Globalism is a great idea but impractical. And Dar al-Islam is not a choice I would personally go for because, well, I do not believe in religion of any stripe.

In our instance, as distinct from the sci-fi story of When Worlds Collide, the colliding is all man-made. So why don’t we un-make it? So long as the different worlds stay in their own orbits why don’t we live and let live? That’s the kind of diversity I favour.

Which leaves unanswered the question of where Flash Gordon has got to. I suppose each world needs its own. Then, each Flash can play Ming the Merciless to the others.

Whaddya think? Shall we take this idea to the UN?

Thanks for reading.

Peter Drucker. Management Challenges for the 21st Century (1999)

Stewart Paterson. China, Trade and Power: why the West’s economic engagement has failed (2018)

Ben Judah. This is London (2016)

Laura Raim. Le Monde Diplomatique (July 2019)

Sridhar Kota and Tom Mahoney. Reinventing Competitiveness, American Affairs Journal, Fall 2019. Volume III, Number 3.

Philip Bobbitt. The Shield of Achilles (2002)

Voltaire translated by Theo Cuffe. Candide or Optimism (1759)

Klaus Schwab & Thierry Malleret. COVID-19: The Great Reset (2020)

Alexander Dugin. The Great Awakening vs The Great Reset (2021)