Understanding how Customer Value shape shifts - have we gone too far with our idea of the marketplace?

Part 2 of a series that aims to help illumine the past to better glimpse the future.

Okay, so where had we got to? Oh yes, Outsourcing. It was the promise of quick returns via increased sales and profitability that led to the outsourcing gold rush of the 1980s, ‘90s and 2000s, For the boards of great numbers of Western enterprises the lure was irresistible, a gold-lined no-brainer.

At the heart of it was what might be termed The Efficiency Promise, a set of new capabilities that was more than enough to squish much longer-term analysis. The promise of efficiency improvements and the quick gains they would produce blinded boards to key strategic issues that might have given rise to at least a modicum of caution. And the elites who drove all this activity pursued their globalization dream with a zeal that really would not take no for an answer.

So it was that, in an astonishingly short period of time, huge tracts of the West de-industrialized. And the key questions that were NOT properly discussed, including:

Is it really wise to outsource everything?

In the early stages of the Outsourcing boom, the explanation from the consultancies who were the more-than-willing overseers of the transition was that it was the grunt work that was being sent overseas - the dirty, boring, polluting, routine work that would, in any event, be taken over any second now by robots and other tech innovations.

This, we were told, would leave high-end, high-value innovation work for Western workers to concentrate on - well-paid work suited to our sophisticated populations.

The problem, however, as might have been anticipated, proved to be that innovation tends to go where the main manufacturing occurs. So, potential problems were soon being reported. This is from an American Affairs Journal of 2019:

Dependence on imports has virtually eliminated the nation’s ability to manufacture large flat-screen displays, smartphones, many advanced materials and packaged semiconductors. The U.S. now lacks the capacity to manufacture many next-generation and emerging technologies.

… In terms of long-term competitiveness, the biggest strategic consequence of this profound decline in American manufacturing might be the loss of our ability to innovate—that is, to translate inventions into production. We have lost much of our capacity to physically build what results from our world-leading investments in research and development. A study of 150 production-related hardware startups that emerged from research at MIT found that most of them scaled up production offshore to get access to production capabilities, suppliers and lead customers.1

By now, of course, we have recognized that there were and are strategic issues arising from the outsourcing gold-rush, including those of national security.

However, the drivers of what was going on were globalists, and globalism axiomatically aims to do away with the nation-state. There’s more about this below but, for now, it seems fair to assume, I think, that, so far as dedicated globalists are concerned there can be no nation-states … and if there are no nation-states how can there be a requirement for national security? See? Logical isn’t it?

Anyway, the article just quoted above also touches on another skimmed-over question …

What will be the social consequences of rapid de-industrialization?

This is to say nothing of the human suffering and sociopolitical upheaval that have resulted from the hollowing out of entire regional economies. Once vibrant communities in the so-called Rust Belt have lost population and income as large factories and their many supporting suppliers have closed. The shuttering last March of the GM plant in Lordstown, Ohio—resulting in the loss of some 1,400 high-paying manufacturing jobs—is just the latest example. ... 2

This question did receive some attention from American legal scholar Philip Bobbitt. In a 2001 work, he explained that he saw the outcome as being a shift from ‘nation-states’ to ‘market-states’.

So what the heck is a market-state?

In the market-state, the marketplace becomes the economic arena, replacing the factory. In the marketplace, men and women are consumers, not producers (who are probably offshore anyway). 3

Yes, okay, if the production work has gone overseas, I suppose its obvious that the citizens of what had used to be a nation-state have to become consumers of that production. But how will they pay for it? What work will be available? Or, to put it bluntly …

What’s to be done with the millions of workers in the West who are thrown on the scrap heap?

To answer this, Bobbitt quotes a chap called Michael Walzer:

What can a hospital attendant, or a schoolteacher or a marriage counsellor or a social worker or a television repairman or a government official be said to make? ... More important than the producers ... are the entrepreneurs – heroes of autonomy, consumers of opportunity – who compete to supply whatever all the other consumers want or might be persuaded to want ... competing with one another to maximize everyone else’s options. 4

Wow! So we’re all supposed to become entrepreneurs, or acolytes to these new priests, in the market-states of the future!

This, to my mind, sums up the whole woolly-headed thinking that drove us all down the globalization pathway. And it gets worse!

Here is a further snippet from Bobbitt’s work:

If the nation-state was characterized by the rule of law – and ... the society of nation-states attempted to impose something like the rule of law on international behaviour – the market-state is largely indifferent to the norms of justice, or for that matter to any particular set of moral values so long as law does not act as an impediment to economic competition. 5

There you have it - the claim for the overarching dominance of the economic function system! Everything subsumed into the marketplace and the rules thereof. Everything!

Regardless of history, regardless of culture, regardless of religion, regardless of anything else … a global economic function system embracing Everything!

My whole career was in Marketing and Sales; I remain a fan of the capitalist system, I think it a powerful force for good; but I do not want Everything to be governed by the rules of the market.

But that’s where we’ve headed because, once the Outsourcing genie was out of the bottle, Western politicians saw it as a means to apply The Efficiency Promise and turbocharge Everything.

When U.S. President Bill Clinton and British Prime Minister Tony Blair, and others, promoted what they called The Third Way (a supposed option distinct from either socialism or capitalism) it seems, ironically, to have included the application of a lot of marketplace rules to Everything.

Not least, it led to the growth of more and more powerful outsourced services providers.

Take, for example, Serco which started out in 1929 as RCA Services Limited, a provider of technical and engineering services to the British War Office.

In 1989, the year that the Berlin Wall came down and Francis Fukuyama published his essay The End of History, the company changed its name to Serco. And now it describes itself as follows:

We bring together the right people, the right technology and the right partners to create innovative solutions that make positive impact and address some of the most urgent and complex challenges facing the modern world.

With a focus on serving governments globally, Serco’s services span justice, migration, defence, space, customer services, health, and transport.

Our core capabilities include service design and advisory, resourcing, complex programme management, systems integration, case management, engineering, and asset & facilities management. 6

Don’t get me wrong: I am not critical of Serco per se or other, similar operators - they’ve found or created a marketplace and I’m sure they serve it well. Good for them.

But I do suggest we need to think about the combined power and effect of service providers (private companies) and non-governmental organizations if and when the net result is increased opacity, lack of accountability and bureaucracy.

So how does this inform the Customer Value issue?

Well, taking it in context with Part 1 of this series, it’s an attempt to describe a major component of the new world that came into being as a result of the West’s assumed victory at the end of the hot and cold wars of the twentieth century.

Outsourcing, enabled by technological developments, was seen to be so practicable, so possible, that it very quickly became applied to Everything. But does that mean that, by definition, it has now gone too far? I think that is a very real danger. We seem to have moved from the smooth-flowing, reliable currents of human interaction and co-operation into the quicksands of bureaucracy.

Which means that, by vastly increasing the scope of that to which we apply marketplace thinking, we may risk side-lining Customer Value.

Why?

Because Customer Value is the value that a Customer experiences in any interaction or transaction. It is, quite literally, the Customer’s subjective experience of whatever is being presented or discussed.

Customer Value is not what a company offers. It’s what the Customer receives.

Some final, brief thoughts about the Outsourcing limitation …

Up until the final quarter of the twentieth century, outsourcing was restricted to discrete functions unrelated to an enterprise’s core business: catering, cleaning, those sorts of things. As far as main business functions were concerned - manufacturing, finance, human resources, sales, and so on - a CEO would no more dream of outsourcing them than he (it was almost always a ‘he’ back then) would have thought of jumping out of the window of his top-floor office suite.

It was the advent of digital technology that changed the game. First, in the form of Enterprise Resource Planning systems (ERP) and swiftly thereafter as functional ‘towers’ provided by outsource providers. And, as noted in Part 1 of this series, and above, the initial trigger in the early days of the outsourcing boom was usually access to cheaper labour.

The boom was turbocharged after December 2001 when China was admitted to the World Trade Organization (WTO). Early in 2001, and right at the end of his presidency, U.S President Bill Clinton gave a speech at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore that included the following:

By joining the WTO, China is not simply agreeing to import more of our products; it is agreeing to import one of democracy’s most cherished values: economic freedom. The more China liberalizes its economy, the more fully it will liberate the potential of its people – their initiative, their imagination, their remarkable spirit of enterprise. And when individuals have the power, not just to dream but to realize their dreams, they will demand a greater say.

Note that last sentence! It clearly demonstrates the belief that, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, we had arrived at ‘the end of history’ - and the belief that the Western economic function system would dominate all others and, in the process, lead to greater social liberalization everywhere.

But it didn’t work out that way.

At its core, outsourcing involved acceptance of an apparent operational contradiction: the more a client company outsourced to an outsourcing provider, the more necessary it became for the outsourcing provider to behave as if it was an integral part of the client company.

However, that meant that as things developed in the twenty-first century with many more outsourced functions across multiple geographies the more complex the whole situation became.

In the early days, outsourcing providers promised clients that they would make it their business to align with the strategy, values and culture of a client company because only then would they be able to assess and respond to technological, economic and market factors that might impact the client company’s strategic goals, as if it were an internal part of the client organization.

But, obviously, there were limits to the practicality of this approach. The whole point about providing digitally-powered offerings was process standardization - specifically, standardization to a defined ‘best practice’.

Not much room for maneuver there, then! So, inevitably, over time, the whole thing got reversed and the power shifted to the outsourcing providers.

This was not necessarily, in and of itself, a bad thing. After all, it meant that the general level of performance across numerous functional areas improved to a new standard.

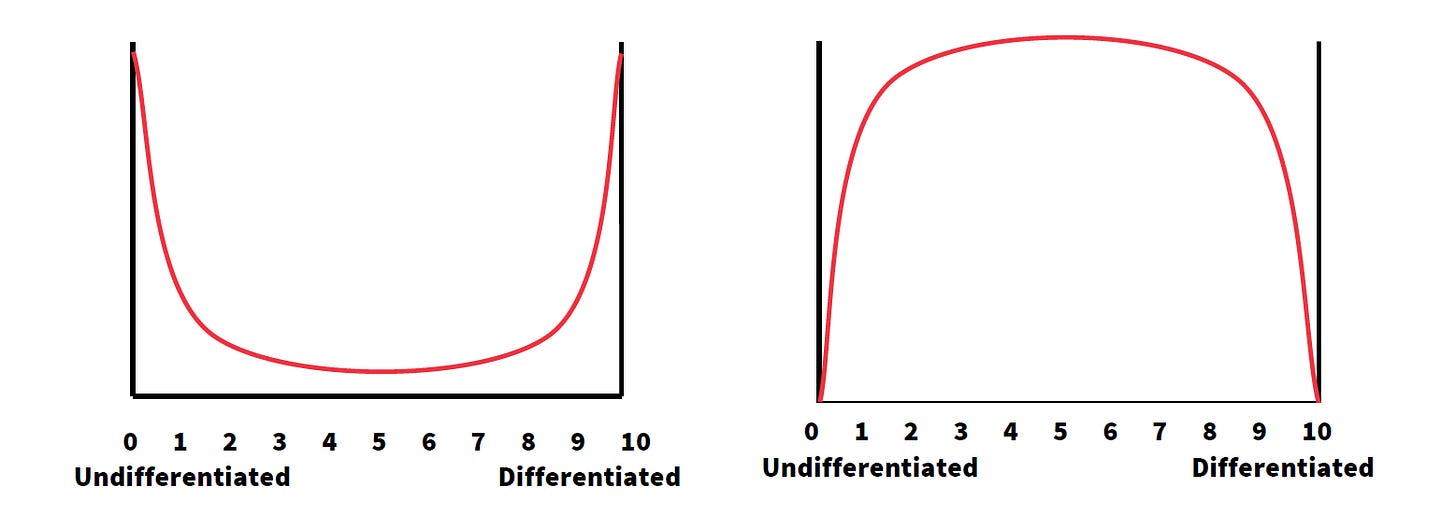

In the 20th century, most products and services were neither totally undifferentiated nor totally differentiated. They were somewhere in between (right-hand diagram below).

However, in the first decade of the 21st century, as digital technology rapidly advanced, increasingly provided through outsourcing deals, the curve flipped over (left-hand diagram above) so that the great majority of products and services became either highly undifferentiated or highly differentiated.

So the average level of performance across the entire range of services increased … but because it often involved ‘standardization’ to a defined ‘best practice’, exceptional performance or new breakthrough performance was far more likely to be ignored.

That’s the point! We have increased the general level of performance across the board but, at the same time, we have put exceptional performance at risk.

Looked at another way, that means, of course, that there’s a hell of an opportunity!

Thanks for reading.

Kota and Mahoney. Reinventing Competitiveness, American Affairs Journal, Fall 2019. Volume III, Number 3. (Sridhar Kota, Herrick Professor of Engineering at the University of Michigan and executive director of MForesight. Tom Mahoney, associate director of MForesight.)

Kota and Mahoney. Ibid.

Philip Bobbitt. The Shield of Achilles (2001)

Michael Walzer. The Concept of Civil Society in Toward a Global Civil Society (1995)

Philip Bobbitt. Ibid.

Serco website - https://www.serco.com/about