Fragment 35: The Life & Times of a Social Experiment

Learning how to write copy in the electro-mechanical age.

The previous personal fragment concluded at the point where John Doff and I were about to start a new company. It was John’s idea: he had made the point that, although advertising copy was very well catered for, long copy (brochures, reports, films etc.) was neglected, and this perhaps represented an exploitable market gap.

Well, we went ahead! Write Solutions launched in 1985, working out of a small office at 50 Fitzroy Street, in London, right next door to where I then lived.

It’s perhaps useful to take a a brief look at the status, at the time, of copywriting. Keep in mind we’re talking about 1985, so we’re still in a pre-digital world where, as yet, there is no universal internet, no ‘connected’ computers, no smartphones.

At this stage, although mobile phones have existed for a handful of years, they are just that - wireless telephones you can carry - or lug - around. Read the news on your phone? Watch a movie? Swap messages online with friends? Nah, at this point in time, all of that remains, quite literally, science fiction.

In 1985, both Microsoft and Apple are around one decade old. Amazon, Facebook, and Twitter won’t even exist for several years. You want an app? What are you talking about?

No, this is still the electro-mechanical age, a time of one-to-many communications. An advantage, for advertisers, is the fact that any advertisement, in the press or on radio or television or other mass medium, that really catches the public’s attention, can command extraordinary mass power.

Perhaps, therefore, it should come as no surprise to learn that, particularly in the capitalist-world-leading United States, advertisements are researched to the nth degree - every image and every word tested with consumers to assess their impact.

But this doesn’t always lead to good outcomes. In many cases it just results in ‘safe’, formulaic, uninspiring advertising.

In the immediate post-war period, some folks had already recognized this issue. David Ogilvy, for example, who set up shop in New York in 1948. He made the point to his people that …

The customer is not a moron. She’s your wife.1

And three chaps called Ned Doyle, Mac Dane and Bill Bernbach who came together in 1949 to start a new ad agency called … er … Doyle Dane Bernbach, or DDB for short. They would strongly endorse this sentiment by putting far greater emphasis on the creative idea behind an advertisement, and the ability to tell a compelling story.

The copy talked to the reader as though he were an intelligent friend, not some distant moron, and was self-deprecating rather than self-congratulatory.2

Keeping that point in mind let’s hop back from New York to London …

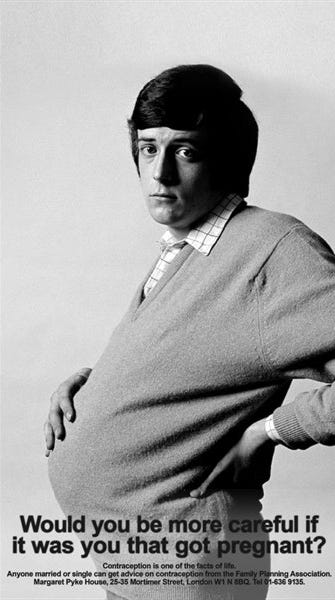

In 1963, DDB had opened a London office, along the way employing a young copywriter called David Abbott. But it was perhaps the arrival of Saatchi & Saatchi in 1970 that heralded the full explosion of talent … or perhaps their national-attention-grabbing first advertisement, ‘the pregnant man’ (pictured below).

Image: Saatchi & Saatchi, 1970 for the UK Family Planning Association.

Then, in 1971, came FGA (French Gold Abbott). Richard French, Mike Gold and, yes, David Abbott, the young copywriter from DDB. However, it appears the team weren’t really a team, so the firm didn’t last beyond 1977. Here is David Abbott outlining the issue as he saw it:

I suppose I felt that I could take the DDB principle with me, and it would still be DDB, but it wasn’t, because I had two other partners who came from different backgrounds, and different philosophies, and so FGA was a good agency but not a great agency.3

Mind you, it wasn’t long before Abbott was back in the game. In 1977 a new formation, AMV (Abbott Mead Vickers), appeared. This was the start of what was to become the largest ad agency in the world.

Then, in 1980, Mike Gold was back, this time with GGT (Gold Greenlees Trott). Looking back on what he termed ‘the sliding doors moments’ that contributed to GGT’s success, Mike made the point, at a 2018 GGT reunion, that …

I think we were lucky that BMP’s [whoops, there’s yet another initialism: BMP stands for Boase Massimi Pollitt] creative director John Webster made a decision about his deputy and heir which didn’t include Dave Trott.

Big mistake.

Huge.

Other initialisms joined the bunfight-for-business, too. For example, WCRS (Wight Collins Rutherford Scott) in 1979, and BBH (Bartle Bogle Hegarty) in ‘82.

There were more, as well, but I hope the point is sufficiently well made that there was a hell of a lot going on in the London advertising scene of the 1980s.

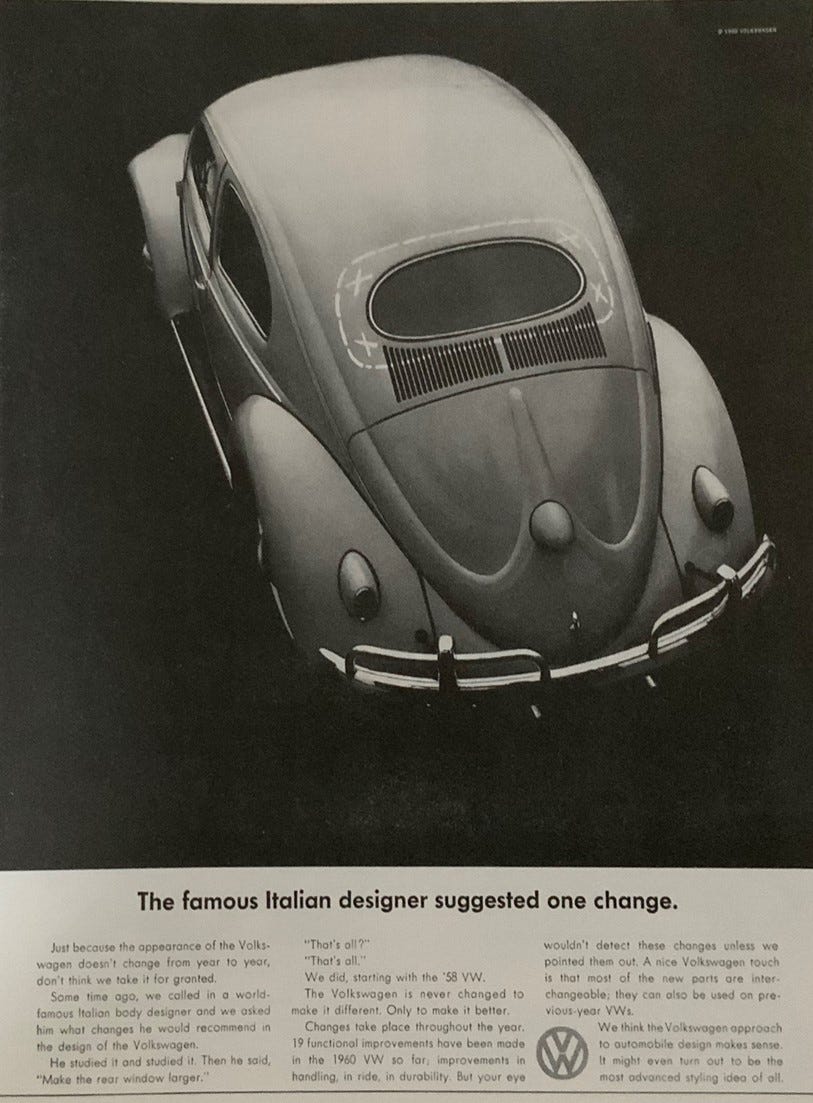

And, to expand on the point made earlier that advertising could treat its customers as intelligent beings, let’s pop back again to 1960s New York and the agency that did so much to demonstrate the power of narrative and words in advertising, DDB, and one of its most famous campaigns, for the Volkswagen Beetle.

The car itself was the brainchild of Ferdinand Porsche - his idea for the German ‘people’s car’, hence volks wagen. During the war years, a factory had been built at Wolfsburg, but no ‘people’s cars’ had actually been built. Only after the war did production start.

But did this this funny-looking little car have any chance of being accepted in America? After all, both visually and mechanically, it was the antithesis of the American automobile of that time.

Nonetheless, in 1959, Volkswagen appointed DDB as their advertising agency in the United States … and, quite simply, it was a rip-roaring success.

Sure, much of that success was down to the car itself, but DDB’s advertising became a real talking point.

So much so, in fact, that in 1982, David Abbott, with Alfredo Marcantonio (another notable copywriter who actually worked at VW for a while) and John O’Driscoll (who moved to DDB as an art director in 1967) created a book that celebrates the VW advertising - “Remember those great Volkswagen ads?”

Right up front, on the book’s cover, they pointed out how impactful these advertisements were …

Office boys read them aloud by the water cooler. College kids recited them at campus parties. They were the marketing conversation piece of the sixties.4

Here’s an example.

Image: DDB, 1960 for Volkswagen. Art director, Helmut Krone. Copywriter, Julian Koenig. Creative director, Bill Bernbach.

Back in London, in 1985, John Doff and I discussed the VW campaign and lots of other ads, and we went to the theatre and cinema to see, and subsequently discuss, a range of plays and movies.

John was, of course, training me to be a copywriter. Sure, my work up until this time had taught me a great deal about sales and marketing generally, but this was a new departure.

Would I be able to rise to the challenge?

Thanks for reading.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_customer_is_not_a_moron

Alfredo Marcantonio, John O’Driscoll, David Abbott. Remember those great Volkswagen ads? (1982)

http://davidabbottsaid.com/abbott/fga.htm

Marcantonio, Driscoll, Abbott (1982). Ibid.