Sustainability ... are we making progress?

Which is to say, are we effectively aligning Value with Values?

Sixteen years ago, on 15 September 2008, the investment bank Lehman Brothers collapsed. It was the clearest possible signal that the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s was under way.

If you’re old enough, you might remember all that stuff about sub-prime mortgages, bank liabilities and what looked, frankly, like unadulterated greed? And, boy, did it drag on.

At the time, much of it seemed incomprehensible - to me, anyway - until a brilliant educational film came along in 2016 and explained some of it. Actually, it was better than your normal educational film. Far better. It was a biographical crime comedy caper titled The Big Short, featuring Christian Bale, Steve Carell, Ryan Gosling and Brad Pitt. If you haven’t seen it I do recommend taking a peek.

But I digress a little from my intended topic.

In 2009 and 2010 the effects of the financial crisis were being felt right across the world. In particular, the concern had to do with rising prices. The cost of living shot up. Not too dissimilar from today, it might be argued.

It was then realized that this was negatively impacting efforts to promote sustainability. Fifteen years ago, the pursuit of sustainability was in an earlier stage of its development and the financial crisis forced everyone to confront a new question:

Does sustainability in product and service development, creation and delivery inevitably lead to higher pricing? Or are we able to produce the goods and services without demanding a price premium?

At the time I was asked by a global management consultancy to write on this topic. Recently, re-reading the piece, I thought it stood up tolerably well and was worth another airing. So here it is, with a few excisions to reduce the length.

Do, please, keep in mind that it dates from 15 years ago. The question is, does it inform the present in any way? You be the judge.

The rise of the Frustrated Consumer: and the imperative to Align Value with Values

The fact that consumers are seeking out cheaper brands to cut costs is a predictable outcome of the economic downturn. Less predictable, however, is the frustration that a significant and growing number of consumers experience as a result of trading down. They are concerned that choosing cheaper brands may compromise their commitment to sustainability.

These ‘Frustrated Consumers’ refuse to accept that economic volatility is any reason to jettison their principles for the sake of expediency. They want quality, availability, price and sustainability.

It is important that enterprises face this issue, not least because it represents a substantial and welcome growth opportunity, whereas causing frustration does nothing to help acquire and retain customers.

What is the root cause of the Frustrated Consumer’s frustration? The answers to this question seem to center on two fundamentals of human interaction – Trust and Value. Before addressing those issues, it is worth taking a brief look at consumers’ opinions.

Who cares?

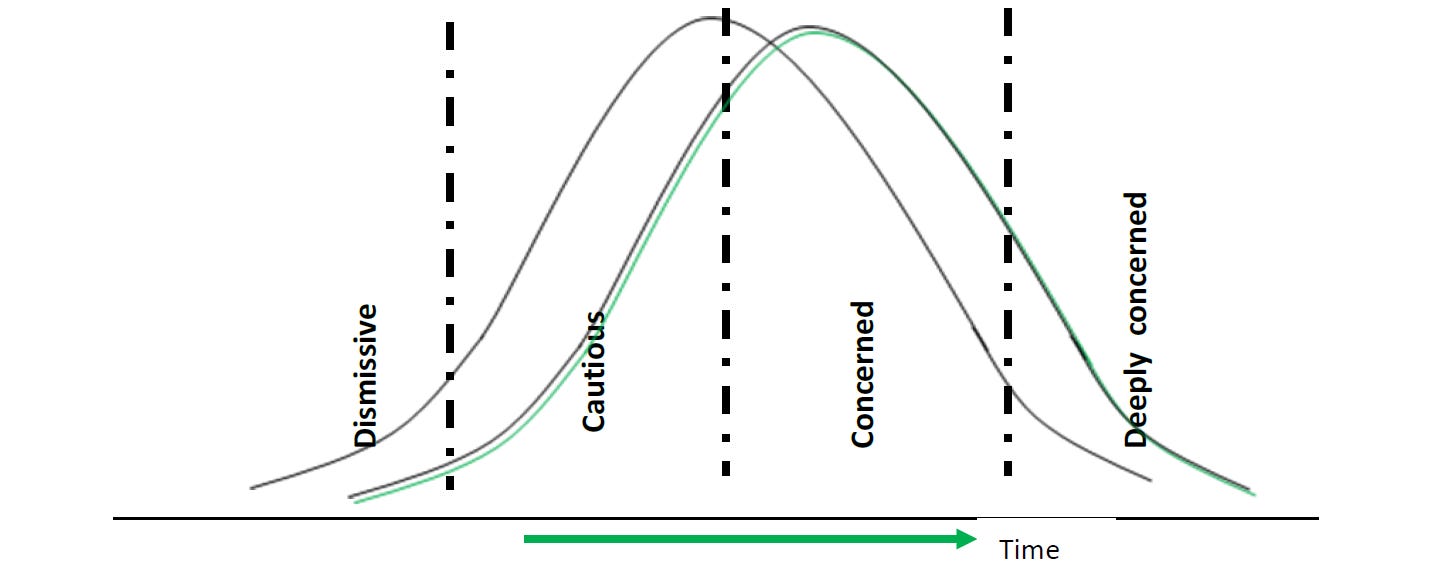

For many human activities, the spread of opinion can be pictured using the familiar bell curve of normal distribution, and so it is with attitudes towards sustainability. The numbers in various surveys differ by a few points, but, overall, the picture is what one would expect.

The evidence is that the momentum created by information availability and awareness is currently nudging the bell curve to the right, which means that an increasing number of consumers are moving into the ‘Concerned’ and ‘Deeply concerned’ categories.

This good news has a clear implication: companies need to respond, now, to consumers’ sustainability concern, recognizing that it is an ongoing, growing trend and an opportunity for competitive differentiation. In any event, as Richard Gillies, Director of Marks & Spencer’s sustainability initiative, Plan A, has pithily put it:

Unsustainable business doesn’t make sense.

More and more, concerned consumers want to engage with companies and products that show active concern for the environment, and everyone in the supply chain, and do not regard it as legitimate to ‘win’ by undermining the longer-term economic prosperity of others. This they regard as good business and, by inference, business that threatens our longer term environmental, social and economic well-being is bad business. So, the consumers’ argument continues, to be asked to pay more to support good practice is illogical because it amounts to being rewarded for supporting bad business practice. Hence their frustration.

The Complexity of Good Practice

To understand the best way forward, it is necessary to understand the causes of consumer frustration. Key among these is the fact that people do not believe they should have to pay extra for sustainable goods and services.

As far as they are concerned, unsustainable business is bad business. Companies of all kinds have a responsibility to go about their businesses in a responsible manner without adding to environmental, social or economic problems now or in the future. Ideally, of course, they want businesses to contribute to improvements in environmental, social and economic conditions.

Recent research shows that only around 10 per cent of consumers trust marketing and advertising messages about sustainability. It’s an abysmal statistic but perhaps not so very surprising. Why do people mistrust messages about sustainability? Three possibilities come to mind. Undoubtedly there are more, but here are three conversation starters:

“SOLUTION SYNDROME” – confusion around the meaning of sustainability

“THE BUTTERFLY EFFECT” – uncertainty around the complexity of sustainability issues

“PROMISE, LARGE PROMISE …” – an historical mistrust of marketing and advertising, probably made worse by current economic conditions

SOLUTION SYNDROME

An element of the mistrust about sustainability messages may have to do with the word ‘sustainability’ itself, its meaning, and resulting confusion in the way that various sustainability messages are given, as, for example, on labeling.

Scientific American tackled the ‘meaning’ issue head on in a March 2009 article titled “Top 10 Myths about Sustainability”:

[S]ustainability is a concept people have a hard time wrapping their minds around. … By all accounts, the modern sense of the word entered the lexicon in 1987 with the publication of Our Common Future, by the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development (also known as the Brundtland commission after its chair, Norwegian diplomat Gro Harlem Brundtland). That report defined sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Or, in the words of countless kindergarten teachers, “Don’t take more than your share.”

That is straightforward enough, but it doesn’t alter the fact that ‘sustainability’ is one of those words that can be applied so loosely that its meaning is lost – a reason for consumer mistrust. Like ‘solution’ before it, ‘sustainability’ runs the risk of being regarded as, at best, an anodyne label and, at worst, jargon. In order to build trust around it, those of us who are champions of sustainability need to be conscious of the danger of misinterpretation, and disciplined and clear in the way that we use the term.

This means that, when enterprises then try to communicate sustainability provenances to consumers via, for example, labeling, there is vast scope for lack of clarity, misinterpretation, and, even, abuse. A recent U.S. article [Taking care of business by Joel Makower] on the labeling topic led with the statement that …

The world of eco-labels these days seems certifiably insane

… typified by utter consumer confusion and mistrust. The author went on to ask:

What will it take for consumers to gain confidence in product certifications and marketing claims? Will a ‘green knight’ step into the picture, introducing a labeling or certification system that becomes the trusted standard?

For sustainability champions these are crucial questions that require urgent answers.

THE BUTTERFLY EFFECT

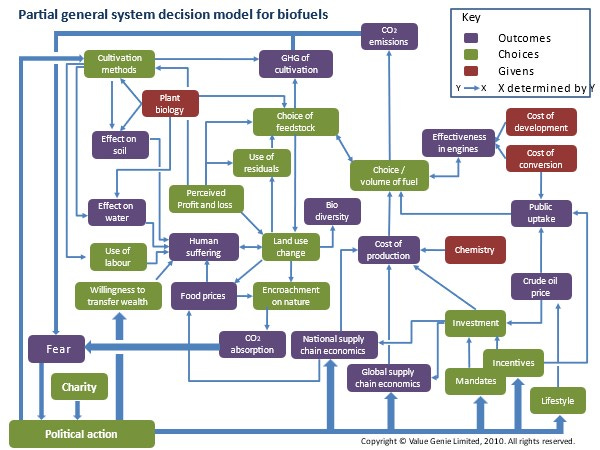

A further possible cause of mistrust has to do with the fact that sustainability involves complex linkages, giving rise to outcomes akin to chaos theory’s ‘butterfly effect’. This is evidenced by, for example, current biofuels developments. Complex connections have recently knocked the shine off the promise of biofuel use. To quote from the executive summary of a major UK review [The Gallagher Review of the indirect effects of biofuel production, UK Renewable Fuels Agency, 2008]:

Biofuels have been proposed as a solution to several pressing global concerns: energy security, climate change and rural development. This has led to generous subsidies in order to stimulate supply. In 2003, against a backdrop of grain mountains and payments to farmers for set-aside land, the European Union agreed the Biofuels Directive. Under this directive, member states agreed to set indicative targets for biofuels use and promote their uptake. Many environmental groups hailed a new revolution in green motoring.

Five years later, there is growing concern about the role of biofuels in rising food prices, accelerating deforestation and doubts about the climate benefits. This has led to serious questions about their sustainability and extensive campaigns against higher targets. Concern was further raised among policy makers when the paper by Searchinger asserted that US biofuels production on agricultural land displaced existing agricultural production, causing land-use change leading to increased net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

The Gallagher Review went on to recommend a slowdown in the growth of biofuels, with lower targets and stronger controls. In the meantime, its continuance fuels criticism, as evidenced by this extract from a Times of London rant [Saturday 18 April, 2009]:

Fleets of ships, belching emissions of sulphur and carbon, are moving ethanol and other biofuels to Britain to ensure that the petrol and diesel sold at filling stations complies with the low-carbon diktat. … It is a trade in bunkum: more ships burning more fossil fuel to move more biofuel in order to burn less fossil fuel.

It makes the points, too, that …

because the amount of diesel available from a barrel of crude is limited, in 2008 4.5 million tonnes of unleaded petrol were shipped from Britain to the United States, and 3.5 million tonnes of diesel had to be brought to the UK, mostly from Russia.

Biofuel crop cultivation has also affected food price inflation and adversely affected the livelihoods of poor people in some parts of the world.

Note: The image at the head of this post, which highlights some of the complexity of globalized supply chains, was created around the time this article was originally written but was not originally featured with the article. Revisiting it, I think it does an excellent job of making the point about complex linkages and the butterfly effect. Thanks to my colleague at that time, Alan Bainbridge, for his work on this graphic.

Thus, a part of the believability challenge that sustainability champions have now to confront stems from the fact that sustainability is multi-faceted. It is usually referred to in terms of three dimensions: X) environmental, Y) social, Z) economic.

This, in and of itself, feeds a possibility of mistrust because a statement containing two or more pieces of information is always less likely to be true than one containing only one of the pieces. Plus, as the biofuels example shows, there is a real risk of the law of unintended consequences coming into play.

PROMISE, LARGE PROMISE

Last in this trio of possible contributors to mistrust in marketing and advertising messages about sustainability is the simple fact that consumers have a long history of mistrusting marketers and advertisers.

Promise, large promise, is the soul of an advertisement …

… wrote Dr. Samuel Johnson in the mid-18th century, and things have not changed much since. In 1836, an issue of the Westminster Review informed readers that “quackery” and “puffing” are the unavoidable consequence …

of a state of society where any voice not pitched in an exaggerated key is lost in the hubbub … mere marketable qualities become the object instead of substantial ones.

The idea of marketing hype goes back a long way, it seems.

Some think that the lack of trust in sustainability messages is part of the current general disenchantment with ‘greedy business’ resulting from the meltdown of parts of the financial services industry. Well, yes, trust may now be at an all-time low, but it was never high.

In the last quarter of the 20th century siren voices did talk about the need for customer-centricity. Peter Drucker was ahead of the field when he pointed out that any consideration of a business must start with the customer. Tom Peters wrote ‘Creating Total Customer Responsiveness’, a rip-roaring thesis that achieved great publicity when it was published [Thriving on Chaos – Handbook for a Management Revolution, Tom Peters, 1987.]

And one of the three foundation points of Hammer and Champy’s seminal reengineering thesis [Reengineering the Corporation: a manifesto for business revolution, Michael Hammer and James Champy, 1993] was “Customers take charge”. But the status quo was all too comfortable: our long-shared experience was of marketplaces utterly dominated by ‘push marketing’ and ‘shove sales’. So, at the start of the 1990s, the late polemical stand-up comedian Bill Hicks got huge applause when he let rip at marketers (the clip has had more than a million hits on YouTube):

By the way, if anyone here is in advertising or marketing, kill yourselves ... There’s no rationalization for what you do and you are Satan’s little helpers. You are the ruiners of all good things.

In 2002, in the period of supposed consumer euphoria that led up to the current difficulties, the late Sheila McKechnie, then chief executive of the Consumers’ Association wrote [in Marketing, 10 October 2002]:

The biggest problem facing today’s marketers is delivering the goods as advertised. The gulf between the marketing promise and the delivery has been stretched to the limit – the promise is now so big and the real value of the delivery so small that the contrast is derisory. So, not surprisingly, many customers have become derisive. Hence the much-cited new, cynical consumer.

From cynicism to frustration is a short journey.

The negative comments quoted above are, admittedly, isolated examples of dissatisfaction – hardly a statistically valid expression of people’s opinions about marketing and advertising. But they touch a chord. A lot of people feel or have felt that way. So much so that, now, when honest and well-intentioned businesses talk about their commitment to, and work towards, sustainability, there is the danger – indeed, the reality – of the messages being mistrusted.

It is vital that those committed to the cause of sustainability recognize the ‘message mistrust’ challenge and go the extra mile to validate their arguments. How best to do this? And, specifically, how best to respond to the concerns of the Frustrated Consumer? The answers stem directly from how, and how accurately, we express that other fundamental – Value.

Value

‘Value’ is another of those words that gets sprinkled liberally across business communications with the assumption that the meaning is self-evident. A prominent application, just now, is its use in the term ‘value proposition’ where, again, the meaning is assumed. It’s a dangerous assumption, for two reasons: One – ‘value proposition’ is frequently and wrongly used as a synonym for ‘benefits statement’; Two: ‘value’ is itself a relative term.

The fact that Value is a relative term means that what Consumer A values may not be of value to Consumer B. Put at its simplest, the sports fixture (or concert, or exhibition, or shopping opportunity) for which Consumer A will pay a small fortune and rearrange his or her life to attend, may leave Consumer B cold.

This problem can only be resolved if we take far greater care about defining the value proposition for any particular consumer or segment, and that is the only way we will be able accurately to communicate the way that sustainability contributes to any product, service or brand proposition. The precision will contribute to building trust.

This means that any service or product proposition must include Costs as well as Benefits, where the Costs include not only financial price but also any perceived or actual risks involved in the purchase. For any purchase, a consumer uses the formula (applied rationally or intuitively) Value equals Benefits minus Cost.

This has a particular force when we refer to sustainability – because sustainability can figure on either side of the equation, as a Benefit or a Cost, or both. As a Benefit, Sustainability is a positive feature. As a Cost, it is the lack of Sustainability that figures.

In a recent article in Green Business, Len Sauers, vice president of global sustainability at Procter & Gamble, made the point that:

It’s very important for us to understand our consumer. According to the data we’ve found on sustainability, a small niche of consumers are willing to accept a small trade off in cost and decrease in performance to purchase and use a product that claims to be environmentally sustainable. And no matter where you are in the world, this number — 7-10 per cent — is about the same.

The vast majority of consumers, 75-80 per cent, will not accept those trade-offs. They are eco-aware, they think the environment is important, but they will not accept a trade off to use one of these products. However, they will reward you if you give them all — price, performance, value and enable them to be environmentally sustainable. They will buy your product.

And then there’s this group that is just indifferent — they are known as the “never-greens.” It’s more than just indifference, they are just not interested in being involved.

Here we have three groups, three high-level value propositions, with Frustrated Consumers possible in categories A and B, but with their most significant presence in category B. Quite logically, Sauers goes on to say that Procter & Gamble is particularly targeting that group:

We are interested in making a meaningful difference, create meaningful improvement. So for us, we are going to target this 75-80 per cent mainstream consumer by offering them what we call sustainable innovation products — products that create a meaningful improvement in the environmental profile of those products but don’t require a trade-off.

An immediately accessible example of a product that transparently includes (relative) sustainability as a benefit is a detergent that works with cold water, a key Procter & Gamble direction. Len Sauers again:

The environmental benefit is substantial. If every U.S. household switched to cold water, 34 million tonnes of CO2 a year would not enter the atmosphere. That would be equal to eight per cent of the U.S. Kyoto targets, if it were a signatory. If every Canadian household switched to cold water, the energy savings would be enough to light up 2.5 million homes.

But what about examples of sustainable product and service development that may not be so clear cut?

The biofuel example quoted earlier shows that the unrestricted pursuit of an environmental goal (progress towards the UK’s compliance with UK and European carbon emissions regulations) could inadvertently lead to increased economic unsustainability (ships criss-crossing the planet, burning fossil fuels) and social unsustainability (people elsewhere being displaced from their land to make way for biofuel crops) and, even, other aspects of environmental unsustainability (the illegal clearance of rainforest to make space for biofuel crop growth).

The butterfly effect must be taken into account. Indeed, the environmental, economic and social dimensions of sustainability must all be pursued concurrently and assiduously. Viz: don’t put your cuff in the butter or knock over the coffee while you’re reaching for the jam.

Up until the last quarter of the twentieth century business and society was far less concerned with people’s welfare than it now is, and there was little knowledge of the environmental dangers that human industriousness was helping to fuel. Consumers either did not overmuch bother or were kept uninformed about the economic and social evils perpetrated in the name of trade and industry.

Slavery is perhaps the most shocking of these factors. But even after the most obvious forms of slavery were outlawed, other forms continued. In his autobiography [Charles Chaplin: my autobiography, Charles Chaplin, 1964] Charlie Chaplin wrote that the genesis of the idea for his 1936 movie Modern Times was …

an interview I had with a bright young reporter of the New York World. Hearing that I was visiting Detroit, he had told me of the factory-belt system there – a harrowing story of big industry hiring healthy young men off the farms who, after four or five years at the belt system, became nervous wrecks.

Today’s version of this issue, of course, is the social unsustainability that requires people, including children, in developing countries to work unacceptably long hours, in unacceptably awful and sometimes dangerous conditions, for unacceptably poor wages so that those of us in the developed markets can acquire low-priced goods.

All of this is by way of a reminder that sustainability is a multi-dimensional issue and that ticking one or two of the sustainability dimension boxes – environmental, social or economic – does not mean ‘job done’. Indeed, where enterprises claim sustainability credentials on the basis of an incomplete ‘audit’, they risk adding to consumer mistrust and frustration.

How, though, are enterprises to ensure that they genuinely deliver holistic sustainability? The answer, which is to build sustainability into the fabric of the organization, is easy to say but not so easy to achieve.

However, unless the entire organization buys in to sustainability as a value that stems from the Strategic Intent, and runs congruently through the Business and Operating Models, to everyday implementation, the best of intentions can – and, usually, will – unravel.

For example, where sustainability is treated as a ‘bolt-on’ rather than a ‘built-in’ element, a procurement executive may quite reasonably source a component, or a product, or a service, based exclusively on functionality and price, without regard to its sustainability provenance … and all the Sustainability Strategic Intent in the world evaporates.

Building a sustainability-committed organization means incorporating sustainability as one of the organization’s fundamental values. This is best achieved by adopting a three-step “3-Vs” model:

Value Proposition

Value Delivery

Value Capture

By so doing, the Value Capture achieved by the organization includes not only direct cash revenue and profit, but also reputational and brand value – including, of course, sustainability. Building sustainability in as a value that permeates the entire organization will progressively demolish consumer distrust and frustration around this aspect of operation.

A key feature of this desirable outcome is the enablement of appropriate decision making – so that, for example, the procurement executive mentioned above would not dream of making a sourcing decision without properly taking account of sustainability factors.

However, this makes decision making more complicated. That can be a problem in an environment where speed of innovation and response, co-ordination of systems, and the ability to create synergy with customers, suppliers and, not least, the workforce, are crucial.

The required positive response is clear: provide greater empowerment for people to make decisions fast. There is no time to keep referring decisions back for approval because corporate agility will be forfeited and competitors will be able instantly to steal several marches. But if more people in the organization have the mandate to make decisions and the requirement to make them faster, how can we ensure that the decisions they make are the right ones – particularly when they include value-based elements like sustainability?

Decision-making and Value Creation

Decision-making is central to corporate performance. It is where value is created or destroyed. It governs resource allocation and the speed at which strategies can be executed. Organizations make countless decisions on a continuous basis, from the solution of simple operational problems to the resolution of complex issues involving tradeoffs between multiple and sometimes conflicting objectives. It is the cumulative effect of these decisions that governs corporate performance.

It is a competitive imperative that organizations move decision-making closer to ‘the customer’ in any transaction. In this milieu, decisions need to be made ever faster and, quite frequently, without complete information to support them. Dynamic customer responsiveness, therefore, carries with it the risk of sub-optimizing performance.

The challenge becomes one of improving responsiveness while maintaining the quality of the decisions that are made. Organizations meet the challenge by process reengineering, new team-working regimes and flattened hierarchies. These measures get things moving. However, seemingly unbridled decision-making licence all the way down the line can be scary.

Nonetheless, enlightened organizations realize that better decisions do not come from greater control, but from better coordination. These enterprises accept that they cannot tell employees what to do in all circumstances. Conditions change too fast for that. Decision-making needs to be made based on broader guidelines. They understand that an environment which promotes the right decisions is critical to executing strategies and maximizing shareholder value. It’s all a matter of making the right decisions.

Can we determine what constitutes a ‘right decision’ and ensure that this is the only kind of decision that people make?

The first part is easy. The going gets more complex thereafter. The right decision is one that maximizes benefits and value to both the organization and decision-maker. And it must achieve those ends while being consistent with the organization’s strategic intent and business model. This requires alignment.

Alignment is the condition where the objectives of an organization are consistent with those of its employees. It is at this point where people feel ownership of the objectives for which they are accountable. And it is this sense of ownership that provides the basis to meet the challenges of today’s business environment.

Think of a tug-of-war team. If they don’t get behind one another and put all their weight into pulling in the same direction in a straight line, they’ll all end up face down, eating mud.

The fully aligned organization has one paramount and unifying objective. Maximizing customer value and thereby maximizing shareholder value. But this can’t be achieved simply by implementing new tools or changing culture. It takes an appreciation of what alignment really means and the levers necessary to reach it. Organizations that understand this do three things which separate their performance from organizations that don’t:

They translate strategy into a market-responsive governance model that clearly articulates decision rights: who makes which decisions and what fiscal boundaries, ethical considerations, corporate beliefs and behaviors are the parameters within which they must be made.

They focus people upon the execution of the strategy by providing the direction and motivation to make the right decisions, act upon them and take ownership of results.

They establish the capability for strategy actually to be executed by providing the necessary information, insight and ability to make right decisions.

Enterprises that are truly value centered in this way create a dynamic work ethic that permeates every level of the organization. Every member of the workforce, from the chief down to the janitor of the most remote company site, exhibits a number of key attitudes: business owner mentality, commitment obsession, a passion for learning (because ‘Experience is the name every one gives to their mistakes’, as Oscar Wilde put it).

Enlightened companies are thinking this way. Procter & Gamble’s Len Sauers, in the interview mentioned earlier, made the point that,

[W]e incorporated sustainability into the company’s statement of purpose, and in a purpose-driven 170-year-old company like ours is, that was a big deal. And it does drive decisions and behavior in the company.

In a paper titled “It’s not easy going green” marketing professor Barbara Khan at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania [February 2007] wrote:

Research shows that in a competitive market, the perception that a company is socially responsible can be a major differentiation point for consumers, but it must be a sincere, deeply held element of the corporation’s culture.

As the P&G example demonstrates, building sustainability in to the Strategic Intent and Business and Operating Models of an enterprise is the only way that the Value Proposition, Value Delivery and Value Capture sequence of the 3-V Model can be fully realized.

From Frustration to Trust

Causing consumer frustration is entirely counterproductive. The challenge that confronts those who are deeply concerned about and committed to sustainability is to replace their frustration with trust.

Now, most people, including most consumers, regard the goal of “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” as being self-evidently sensible and ethically right. That is why current failures to deliver this goal as a matter of normal practice (which includes, of course, no price premium) are giving rise to more and more Frustrated Consumers.

Avoidance of consumer frustration requires us to provide clarity, metrication and reliability. Crystal clarity in the way we describe and use the terminology of sustainability. Scrupulous analysis of the complex linkages that can make or break sustainability initiatives, in order that we are able to fully understand and accurately communicate sustainability provenances. And recognition that these outcomes are ultimately only possible reliably where enterprises internalize their commitments to sustainability as part of a core intent and business model.

Only when these points are actioned can the Value Proposition, Value Delivery, Value Capture sequence of the 3-V Model come into its own to generate value for consumers and enterprises alike. Then, and only then, is there the realistic possibility of building trust, and eliminating the concerns that currently give rise to the Frustrated Consumer.

Well, there we are. Fifteen years on how are we doing?

Looking back, it reminds me how much this was a part of my personal journey regarding the Value Proposition. But I’ll address that in a separate post.

In the meantime, thanks for reading.